January 13, 2011

The Road and the Radio

The streams run out of the higher elevations, veins that let the mountain bleed. The water rushes, tumbles and races to its destiny, to be drunk deeply or left to stagnate in a secluded pool. The sky breaks out in articulate warmth, there on those last days of the conceit of winter. Soon the sky would warm the land, warming me. In the fields, the planting of grain, in the barn, the protective low of a cow with her young.

It was the very end of the 70's. It would soon be Spring, in the year that the fire took down the hillside behind the house, the year the marching band went to State. It was when I learned about freedom and speed, the year I learned to drive.

It was the year in which I learned about the hard outcome of choice.

I'd been emboldened by movement all my life. Looking at my "baby" pictures, there I was in pajamas with feet, racing down the hall. Scribed in the album, a note in my Mom's handwriting -"Always on the move!" When my older brother got his first bike, I wanted one too, though if I could have put a JATO bottle on the back of it I would have been happier. There were skates and vacation boogie boards and sometimes just the rushed dash through a sprinkler, the water dripping from my hair like jewels.

I was captured by movement, machinery and speed and now there were keys in my hand, a vehicle just waiting to take all of our compressed heat and explode it into sound.

Dad taught me the basics. My older brothers taught me the essentials. I didn't just learn how to drive, I learned how to drive in the snow, in driving rain, in the ice to get out of a skid. I could do cookies in the snow out in the middle of a large deserted parking lot all day long if they let me. Someday those skills would save my life.

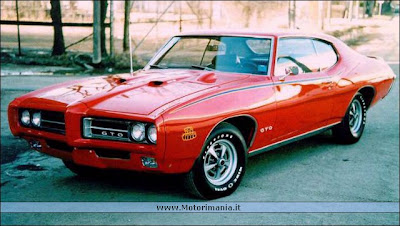

I had visions of what car I wanted. an old muscle car or high performance vehicle. I didn't want some safe, placid girl car, I wanted THIS.

Or perhaps a 68 Camaro, 66 Vette, 67 Barracuda. Classics of past decades. Probably not likely to happen on a buck an hour babysitting (though I got the Cuda 10 years later). No, I got a dinged but reliable, hand-me-down 74 Volkswagen Bug. Not exactly what I had planned. Even worse, it had no radio. No radio? Dad said when he bought it, he had the choice of the radio or the locking gas cap and went for the cap. Soon we had an 8 track tape player squirrelled under the dash out of sight and I discovered that you CAN put glass packs on a Volkswagen if only to crank up the annoyance factor of being a teenager.

Dad set a few rules. We would pay for our insurance if our grades fell below honor roll. We paid for our own gas and any damage. If any of the kids got the lecture about drinking and driving it wasn't I. Koolaid was still more my style. But I'd drive. Oh Lord, I'd drive, miles and miles with the window down, drawing in deep breaths of freedom, the wind in my face. Dad did check on me, once chuckling with "so it takes 33 miles to go to the library and back?" Dad was just lucky we weren't out trying this (which we could have if we could have gotten away with it).

Then came the day I came home from school and said I wanted to learn to fly a plane. I could get my license at age 17. Let's just say I was met with less than enthusiasm. After the not so gentle reminder that he was not going to pay for it, Dad told me his concerns. He loved me, but said he didn't believe me able to cope with the extra studies of that, combined with school work and the hard task of fueling the planes to pay for my lessons. Physically, out in the elements, a lot harder than any other part time job I had. My first day, getting checked out to drive the big fuel truck to take care of the King Air's and small jets that came in on a 7 degree day, my Dad told the family I wouldn't last the week. I did.

With my red hair and Celt ancestry the pilots called me the "Gas Lass" but there were many days I'd come home, reeking of JP4, so exhausted, battered and sore I wanted to cry. So I'd sit alone in my room and say out loud "I'm going to be a pilot" just listening to the sound of it, the discord between a parents words and mine. And I stuck with it, paying for it all myself, never having my toys or education handed to me on a platter with a VISA card like so many of the kids today.

The hard physical work, the challenges, helped us grow up. I think mastering a machine, be it of the aerial or earthbound type, was a turning point. Responsibility, wonder. I looked down an open road and see only possibility. I could stand next to the runway and smell it, the wind and the ice of physics raining down and however much I loved this open new world I knew it was not a sheltered one. The world can wrap its benign arms around you, then without feeling, cast you to your death. It was not a place for fools or sissies, even as I soloed at age 16, I realized that.

Soon my friends were driving with bigger, faster cars, and the speed would increase. We even found a road where if you hit this rise just so, and at a certain speed and angle, you could go airborne, aka Dukes of Hazard. We drove off into the hills with that sense of immortality that only the very young and the very stupid seem to have. Driving without fear, without thought, sacrificing only some rubber and the occasional fender to the gods of the roads.

I learned to do burnouts and donuts, and once, when I came upon a boy I thought was mine, to find him with someone else, I learned to spin out quietly from a driveway with noise that makes no sound, no wound on the drive of pavement or motion, just the soft shuddering sound of the tear of raw silk. We were teens, there was tears and drama, hook ups and break ups. It was the season of curving roads and youth, where we were immortal, no adult responsibilities to block that open road.

On those free afternoons we'd pile in the cars, heading up into the hills to seek the source of the water and ride it on down. Cresting the hills with windows open, the wind as fluid, hot and hard as love, a swift current that will pull you under, to drown, gasping. We'd drive for miles with just the sensation of rushing space as deep as the water. We'd drive until dark, unrelenting and unrepentant, curfews nipping at our heels, leaving only in our wake the sound of cicadas and the breathing of night taking in the remnant smell of high octane.

Soon enough there would be graduation and college, likely sans car to cut expenses. These days would vanish with a mute, befitting, hollow sound, which would drive for only a moment upon us, with the dreadful still hush of motion stopped, too abruptly to mourn. Adulthood looming where vehicles became simply transportation again, something to shuffle kids around, a transport to work. We could not comprehend that someday, for many, life would become an emptying suitcase of enthusiasm. We swore if we ever had to buy a station wagon we'd kill ourselves.

We had our future, we had our past and in those moments, as wheels hit the pavement, and gravel flew, sometimes we had both at once.

It was once said in an age-old axiom, that an object cannot occupy two positions at the same time Perhaps in those microscopic realms beyond any conceivable experiment of physics it will be possible somewhere, there in the darkened edges of our life, where quantum mechanics reaches out to the human world. And we could be in two places at once. Or occupying the same position at two different times. Or fervently wishing we could

On weekends I still worked at the airport to pay for my lessons. Other days, I had a part time job in the local funeral home, doing some light bookkeeping, dusting the caskets in the display room, mostly being there to answer the phone and provide coffee and comfort if a family came in late at night. I'd work a 12 hour shift, noon to midnight a few days a week, an easy summer work for more than minimum wage, though my friends teased me about my choice of jobs. The call came in late, two brothers, in a small car, not unlike mine, hit head on as they crossed the center line on a curve marked "no passing".

I was there when they brought them in. Though I didn't know them really, just remember seeing them around town in their car. I had more than one evening in their company there at the funeral home, wondering if they had second thoughts of their decision as they slept suspended within the hard vaults of their regret.

Would they have made the same choices if they'd known? We've all had days like that, when simple things went awry, plans made that mattered little to you, mattered much to others, things said, bridges burned, moments that repeated themselves for weeks or months in your head. If only I'd done this, if only I'd said that. Moments in which you wish you could turn back on itself, as if you've never been there. Moments that repeat themselves in your memory, minute by minute, wrong place, wrong time.

After that local tragedy, our parents lectured us about the dangers of speed, of road signs and why they are there. Some kept their kids grounded, not allowing the to drive at all. Certainly such a place is safer; where no smudge of desire affects debate, prediction is not contaminated by untried theory and actions aren't clouded by concealed agendas. Still, it is a world flat and colorless as tap water. It's a world whether hiding at home or out with the wind in your face we pass an anniversary without awareness. That of our own passing.

My Dad did not lecture, he knew what I'd seen was its own lesson. In a life fully lived we engage our fate deliberately, we speak the words we may later regret, but we have to say them. We engage life as a indefatigable opponent that others will wish to tiptoe by, so not to awaken it. We risk our necks, and we risk our hearts, both. So although I slowed up, it was not by much. But I didn't make it to 21 by not scaring the wits out of myself, in a car, and in that little airplane I flew on the weekends

We've all had that experience. The one that makes you reticent to get back near what caused the situation in the first place. "Getting back on the horse" as they call it. Sometimes it's a near accident, sometimes it's the real thing. One of those days that was meant to be spent in quiet order when suddenly fate reaches out place its hand on your shoulder, sometimes a reminder, sometimes an order home. The earth is full of fight and friction but when that moment happens, the world hangs motionless in the moment, a cooling mass in space, even as you articulate your sudden surprise.

Sometimes you get lucky and survive, but the event leaves physical scars. But for most, the scars can't be seen and can only be traced by gentle hands, with hesitant trepidation, somewhere in the dark.

I learned that as a teen, as I dusted the coffins of those who had lost their particular battle. I learned later, as I studied the bones and pieces of life past and present, that fate is, and always will be ravenous for the flesh of the foolish, rarely frustrated or even thwarted. It sits and waits with great patience, for yesterday and today are the same to it, indivisible, timeless. Sometimes it slumbers under God's stroking hand as He watches like a parent from a distance as we do something particularly foolish, sometimes it wakes hungry, alone and seeking.

I have been witness to that too many times. The phone has rung and I've grabbed gear and bag, tox boxes and survival equipment. The vehicle is as high as mine, four wheel drive, needed where I'll go. The cold echoes off the pavement in which the only shadow is its form. It's a large truck, extended cab, with a short bed. Much like my truck at home, but that one doesn't have the cool little lights on top to get the gawkers off the road ahead so I can go to work.

I have been witness to that too many times. The phone has rung and I've grabbed gear and bag, tox boxes and survival equipment. The vehicle is as high as mine, four wheel drive, needed where I'll go. The cold echoes off the pavement in which the only shadow is its form. It's a large truck, extended cab, with a short bed. Much like my truck at home, but that one doesn't have the cool little lights on top to get the gawkers off the road ahead so I can go to work.

As I climb in, I catch a reflection in the side window of my truck and see my own face. The face is of an adult, yet overlayed with the the plaintive need of the youth in all of us, seeking release, wanting to leave a parent's watchful eye and just feel the world soar past. I silently open the truck door, as if sneaking out, and fit my form into the leather seats, an old familiar embrace which no amount of days or a few extra pounds can change.

With a shuddering tremble of a racehorse at the gate, the truck backs out into the drive.

I have no curfew. My Dad is slumbering a thousand miles away and won't be waiting up for me. I might be home in 6 hours. I might be home in 20. For now, it's just me and my ride, miles of road interspersed with the angular cuts of barren fields, ringed with blue sky, windows rolled up as a futile barrier to the cold. As the truck moves onward, snow begins to fall. I watch the side of the road as ghosts of those who risked all, wave at me from tiny markers that note their passing, and my foot comes off the gas, the snow falling with astonishing clarity.

You need to look close as you balance the deep satisfaction of taking a risk and winning, with the need for caution; for weighing all the odds, the options, the infinity of what you are launching yourself into, is not easy.You take a risk of losing your life or losing your heart, both with consequence, both risks sometimes worth taking.

The snow hits the hood and melts, swimming like dew before a rush of air. One moment life and form, then the next melting indistinguishably into the wind. Ahead is only the miles, with nothing to do but take in the occasional broken road sign and empty barns breaking up those small patches of cleared earth, whorled with hard work, small square islands of grain. The air is cold with the white smoke of brittle leaves, snow on the ground, fire in my heart. Up ahead a horizon, up above a sky, inscrutable, desolate above the land it looms. Staying home won't make you safe, any more than ignoring the world will somehow make it safe.

I'm wondering if this rig will go airborne if I hit the rise just so, but I don't. I'm entrusted with its use, and I'll treat it like my own vehicle, with the wisdom of miles, knowing when it's time to speed past that demarcation between what I should do and what my heart tells me to do. Calculating the miles the speed, the wind, the traffic, weighing the risks of life versus loss. The passing landscape is bounty and beholder, the open road its postulate. The asphalt flows past, as do the signs, of feed stores, of gas stations, of tiny fixed crosses there by the road. Reminders that despite our freedoms there are lines you that are written into infinity. Once you cross them, you can never go back.

--Brigid

You write so well and evoke such memories, thank you.

Posted by: Merry at January 13, 2011 11:50 PMWell written. You chose the bold path - not the easy road.

'Reminds me of a slogan from my Army Infantry days:

"You have never lived until you have almost died. For those who fight for it, life has a flavor that the protected will never know."

Nice essay Ma'am- hope you keep writing them.

Posted by: backhoe at January 14, 2011 06:50 PM